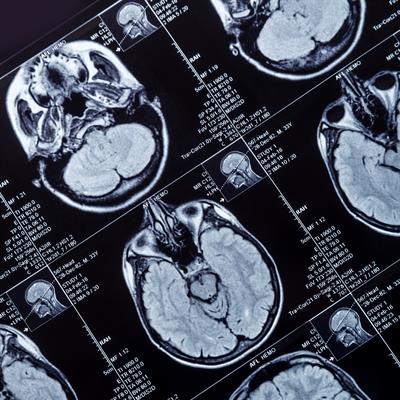

September 26, 2022 -- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is funding research into the repurposing of the breast cancer drug letrozole for use against the most deadly form of brain tumors.

Letrozole, which was sold by Novartis as Femara, won U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in 1997. The product label covers the use of the aromatase inhibitor in three breast cancer indications. However, a team of researchers at the University of Cincinnati (UC) has spotted an opportunity to repurpose the drug for use in the treatment of glioblastoma, an aggressive, hard-to-treat form of brain cancer.

The NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has signed up to fund the work. The $1.19 million, three-year NIH grant will support preclinical assessments of the effectiveness of combining letrozole with other chemotherapy compounds.

In breast cancer, letrozole works by targeting an enzyme, aromatase, that is found in breast cancer cells and helps the cancer to grow. Pankaj Desai, PhD, began assessing whether aromatase plays a similar role in glioblastoma in 2012. Early attempts to answer that question found that the enzyme was present in brain tumor cell lines. Further work showed the samples contained a very high amount of aromatase at protein and mRNA levels.

The discoveries suggested that aromatase inhibition may be effective in glioblastoma. However, the tumors are harder to access than breast cancer because they are behind the blood-brain barrier, meaning that only molecules capable of crossing the blockade will be effective. That led Desai and his collaborators to letrozole.

"There are other compounds similar to letrozole, but we went with letrozole because we figured that based on its properties, this compound actually has the best chance of getting through into the brain from the blood circulation," Desai, professor and chair of the Pharmaceutical Sciences Division in UC's James L. Winkle College of Pharmacy, said in a statement.

While studies in animal models showed that letrozole was effective, Desai's lab tested the compound in cells derived from human brain tumor tissues.

"What we saw in the patient-derived cells is that letrozole is very effective in killing the tumor cells in cell culture models," Desai said.

Based on the preclinical findings, the researchers began a phase 0/I clinical trial to generate data on the letrozole dose that will be needed to treat glioblastoma. Preliminary results from the trial, which is nearing completion, show the drug reaches its target in the brain and needs to be given at a higher dose than in breast cancer.

Although the findings suggest letrozole may have some effect against glioblastoma, the researchers believe a combination of molecules will be needed to tackle the tumors. That thinking led to the request for NIH funding of assessments of potential combination therapies.

"By investigating possible combinations with letrozole for GBM therapy, this new project has the potential for faster translation to clinical trial," said David Plas, PhD, Anna and Harold W. Huffman endowed chair in glioblastoma experimental therapeutics in the Department of Cancer Biology in UC's College of Medicine, whose research group has joined Desai's team for the new NIH-funded project.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net