October 13, 2022 -- Scientists have developed an organoid transplantation method integrating human cortical organoids into developing rat brains that may allow more detailed examination of the brain processes involved in neurological and mental disorders.

The study, published October 12 in the journal Nature, was funded by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the findings suggest that transplanted organoids may offer a potential tool for investigating the processes associated with disease development.

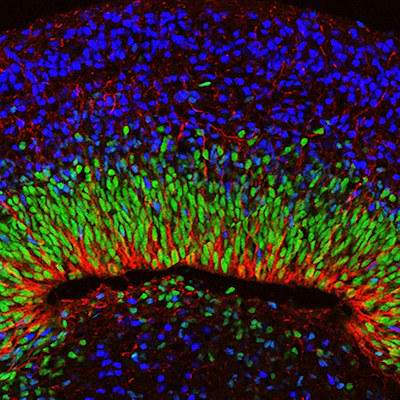

Cortical organoids, often used as human brain models, lack the connectivity seen in human brains. NIMH researchers advanced cortical organoids' usefulness by culturing them from human stem cells and then inserting them into the primary somatosensory cortex of developing rat brains. Blood vessels from the rat brain supported the implanted tissue, which grew over time without causing motor or memory abnormalities.

To understand how well the organoids could integrate into the rat brain, the researchers infected a cortical organoid with a viral tracer. After transplanting the marked organoid, researchers detected the viral tracer in multiple brain areas.

The researchers also observed new connections between the thalamus and the transplanted area, which were activated using electrical stimulation and stimulation of the rat's whiskers. In addition, they were able to activate human neurons in the transplanted organoid to modulate reward-seeking behavior, indicating functional integration of the transplanted organoid into specific brain pathways.

To find out whether transplanted organoids could shed light on human disease processes, the researchers generated cortical organoids from cells from three participants with Timothy syndrome, a rare genetic disorder, and three participants without known diseases and implanted them into rat brains. Both organoid types integrated into the rat brain, but Timothy syndrome patients' organoids displayed structural differences that did not appear in similar cell-cultured organoids.

This work "allows organoids to get 'wired' in a more biologically relevant context and function in ways they can't do in a petri dish," said David Panchision, PhD, of NIMH, in a statement.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net