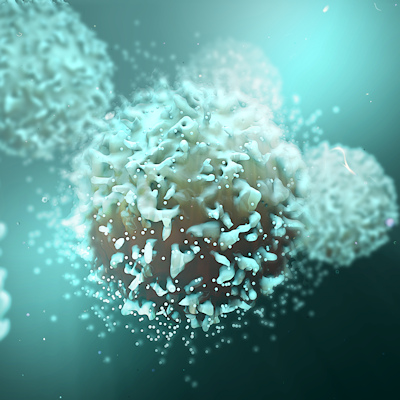

September 8, 2022 -- Stanford University researchers built a complex and well-defined synthetic microbiome with 100 bacterial species that they successfully transplanted into mice. The creation of the synthetic microbiome means the scientists will be able to add, remove, and edit individual species so they may better comprehend the links between gut microbiome and health.

Microbiome transplants usually originate from fecal matter, but tools do not exist to remove or modify one species among the hundreds in a given sample. To remedy this problem, Stanford researchers built a microbiome from scratch by individually growing and then mixing constituent bacteria (Cell; September 6, 2022). To do so required a tricky balance of not only bacterial stability, but also functionality.

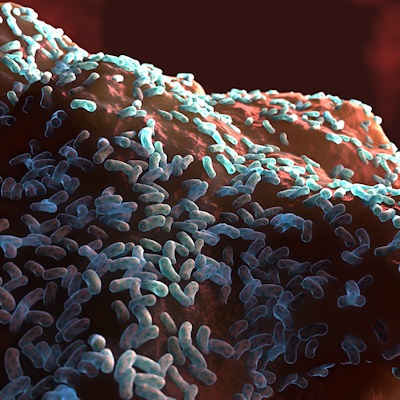

The scientists built the colony from the most prevalent bacteria and crosschecked them with the Human Microbiome Project (HMP), a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative to sequence the full microbial genomes of over 300 adults. The researchers tried to find the bacteria most prevalent in the human gut and selected more than 100 bacterial strains present in at least 20% of the HMP individuals. They grew bacteria in individual stocks and then mixed into them one combined culture to create "human community one" (hCom1).

They introduced hCom1 to mice with no gut bacteria and discovered 98% of the constituent species colonized the gut of the mice with relative constancy over two months. The researchers also added a human fecal sample to their colony to track whether new species took up residence. They found that only about 10% of cells in the final community came from the fecal transplant.

Adding and removing bacteria based on the addition of the fecal transplant sample and bacteria that failed to flourish left the scientists with a new community of 119 strains (hCom2), which made mice even more resistant to other bacterial colonization. For instance, the colony held its own against a sample of E. coli.

The research team plans to narrow down which bacteria are most critical for a healthy gut; doing so could make engineered microbiome-based therapies possible in the future.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net