July 18, 2022 -- Using single-cell genetic analyses of frozen brain samples, Columbia University researchers have uncovered evidence of how melanoma brain metastases evade current treatments.

In a study published on July 7 in Cell, the researchers describe the use of single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and matched spatial single-cell transcriptomics and T-cell receptor sequencing to analyze more than 100,000 cells.

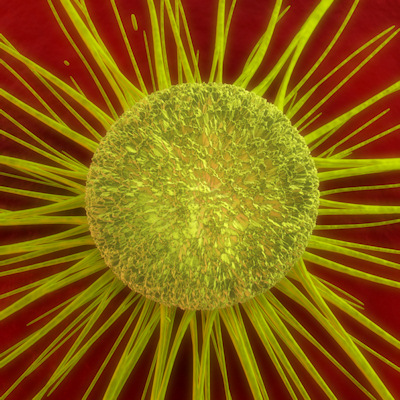

The analysis found brain metastases are more chromosomally unstable than melanoma cells in other parts of the body, suggesting their drug resistance may stem from their ability to suppress the immune response.

Immunotherapies have improved outcomes in melanoma patients, but brain metastases remain hard to treat. To understand why melanoma spreads and resists treatment, researchers at Columbia University sought to gain insights into the underlying biology of metastatic cells.

Most single-cell genetic analyses use fresh brain samples, but they are in short supply. The Columbia team overcame that bottleneck by adapting the processes to frozen samples, thereby enabling the use of the ready supply of samples in its tissue bank. The study looked at 22 treatment-naive brain metastases and 10 extracranial melanoma metastases.

Comparing the brain and extracranial samples revealed differences in chromosomal stability, a term that describes the gain and loss of large chromosomal fragments. The chromosomal instability seen in the brain metastases "triggers signaling pathways that make cells more likely to spread and better able to suppress the body's immune response," said Dr. Johannes Melms, one of the study's first authors, in a statement.

The finding points to a way to improve outcomes in patients with melanoma brain metastases. Melms and his collaborators know of several experimental drugs designed to reduce chromosomal instability that are scheduled to be tested in humans soon. The study provides a rationale for enrolling melanoma patients with brain metastases in the studies.

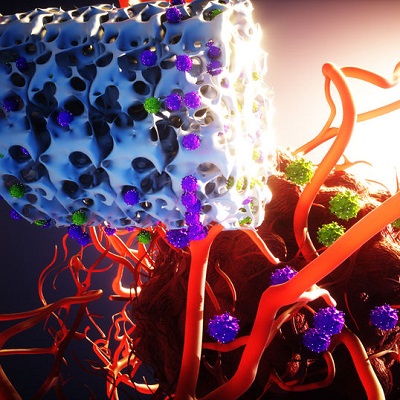

Chromosomal instability is one of several ways that melanoma brain metastases may evade attack by the immune system. The study also found the metastases may alter macrophages and T cells in the tumor microenvironment, thereby promoting cancer growth, and "adopt a neuronal-like state inside the brain."

The final stage of the study consisted of a spatial analysis of melanoma brain metastases. The researchers pieced together analyses of multiple slices of the tumors to build a picture of the differences within metastases.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net