September 12, 2022 -- Researchers at Boston University have created on and off switches for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, enabling them to control the activity of therapies using an approved drug.

CAR T cells are a powerful anticancer modality, but first-generation CAR T-cell treatments are hard to control. After administration, the cells can overstimulate the immune system, causing potentially fatal adverse events such as cytokine release syndrome. While physicians have developed ways to mitigate the side effects and reduce the rate of severe outcomes, they still lack the means to turn the cell therapies off completely.

Multiple R&D teams in academia and industry are working to provide that level of control. The goal is to make CAR T-cell therapies more like conventional treatments, in that physicians can dial the intensity of the intervention up and down incrementally after seeing how patients respond.

Researchers at Boston University posted details of their contribution to the effort in a September 8 article in the journal Cancer Cell. The paper describes the development of edited T cells, called Versatile ProtEase Regulatable CAR T cells (VIPER CARs).

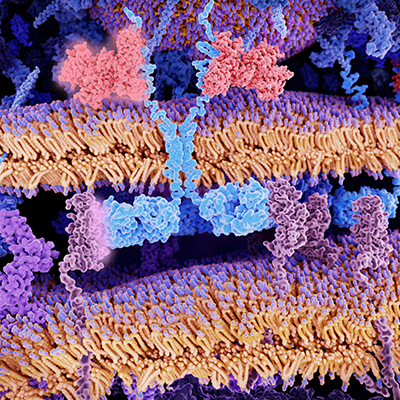

Like other CAR T cells, VIPER CARs feature a receptor that crosses the cell membrane, with part housed inside the cell and part outside. The portion of the receptor that is outside of the cell binds with cancer antigens, activating the T cell and driving the destruction of cancer cells.

VIPER CARs feature an additional protein chain. When a protease inhibitor interacts with the protein chain, it triggers reactions that, depending on the design of the CAR, either switch the therapy on or off. Multiple protease inhibitors, such as Incivek and Mavyret, are approved in indications including hepatitis C.

"That is the most exciting part of this study, that the antivirals are already FDA approved," Huishan Li, PhD, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at the Boston University College of Engineering, said in a statement.

The researchers validated their VIPER CARs in a xenograft tumor and a cytokine release syndrome mouse model. Pitted against other CARs that can be deactivated by drug molecules, the researchers found that the VIPER CARs delivered best-in-class performance.

Building on their success, the researchers combined various CAR technologies to engineer several VIPER CAR circuits. The therapies could target two different receptors, reducing the risk of cancers nullifying their effectiveness through antigen escape.

"We see this as the next generation of this type of therapy," said Wilson Wong, PhD, a Boston University College of Engineering associate professor of biomedical engineering. "We not only have a safety control in place, but we also can have multiple versions at the same time."

Having shown that the VIPER CARs work in cell cultures and in mice, the researchers are now undertaking further development with a view to ultimately testing the technology in humans in clinical trials.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net