February 27, 2023 -- NYU Langone Health researchers found in a study that the number of specialized immune cells available for fighting skin cancer doubled when a new treatment blocked their escape from melanoma tumors. The study, published February 27 in Nature Immunology, found that combining an immune cell exit blocker with another immunotherapy drug stopped melanoma tumor enlargement in more than half of the mice tested.

Recent advances in immunotherapies -- medications designed to help the body's immune system detect and kill cancer cells -- have greatly improved cancer treatment. Immunotherapies boost the action of immune cells that directly attack the cancer, while also preventing cancer cells from evading recognition by the immune system. The latest generation of immunotherapies, called immune checkpoint inhibitors, protect anti-tumor T cells from inactivation and have become a mainstay in melanoma treatment. Previous research showed that having more T cells overall, particularly in the centers of tumors, increases the drugs' efficacy.

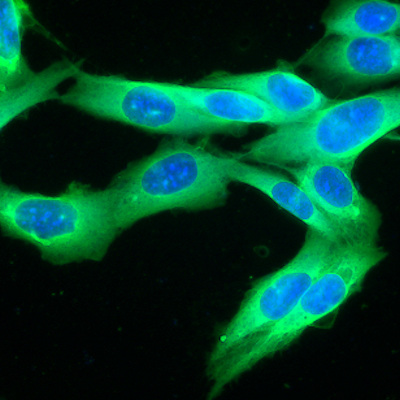

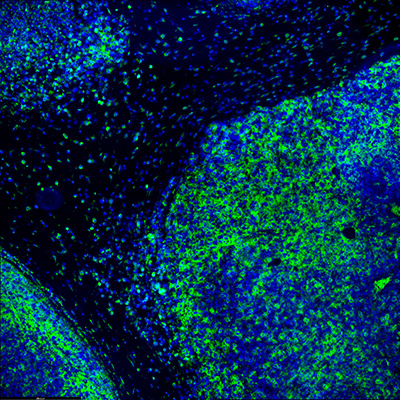

Researchers conducting the study found that key immune cells, called CD8 T cells, escape melanoma tumors when they gather near the tumor periphery and nearby lymphatic vessels, which carry immune cells throughout the body. In mice bred to lack lymphatic vessels, more T cells accumulated inside their tumors.

Further experiments showed that the signaling molecule chemokine CXCL12 and its related receptor protein CXCR4 attract and move T cells toward lymphatic vessels. The T cells are likely drawn to the tumor's outer rim, closer to the lymphatic vessels, by CXCL12.

CXCR4 then encourages the T cells to exit the tumor. When either CXCL12 or CXCR4 was blocked, T cells could not emigrate from the tumor and instead stayed in its center. When researchers combined immunotherapy with a chemical CXCR4 blocker, T cell numbers in mouse tumors doubled and half the tumors stopped growing.

They also found that T-cell leakage depended on potency. The longer the most potent T cells spent inside tumors, the more likely they were to encounter their target cancer cells and remain inside the tumor. Therefore, increasing the initial time these T cells spend inside the tumor may improve therapies.

The researchers concluded that since the lymphatic system likely recirculates T cells out of tumors, blocking the exit signals with either CXCR4 and/or CXCL12 might shift the balance toward keeping T cells inside tumors long enough for immunotherapy to work for some patients. Future research will investigate how blocking T-cell exit influences immunotherapy, and how targeting other molecular pathways in the lymphatic vessels might increase the T cells' dwell time inside tumors.

"Our study shows that blocking this escape route lets immunotherapy work better in fighting the growth of skin cancer cells," NYU associate professor and senior investigator Amanda Lund said in a statement. "These results suggest that it is not only about getting T cells into the melanoma tumor but also about getting these T cells to the right place with the right signals to drive the most specific and durable immune responses."

Copyright © 2023 scienceboard.net