September 15, 2021 -- Engineers have developed a new gel that supports the growth of tiny replicas of the pancreas from healthy or cancerous pancreatic cells. The breakthrough could help researchers develop and test potential drugs for pancreatic cancer -- one of the hardest types of cancer to treat -- according to a study published September 13 in Nature Materials.

In vitro 3D approaches, such as organoids grown from mouse and patient-derived tumor cells, are essential for investigating therapeutic approaches to fighting cancer because of their ability to mimic the pathological properties of a real tumor environment in the laboratory.

The organoids are grown in a tissue-derived gel substrate placed in a lab dish. Traditional gels -- comprising a complex mixture of proteins, proteoglycans, and growth factors derived from actual mouse tumors -- can be temperamental to work with, with the quality and purity of the gel varying from lot to lot. There is no guarantee that a specific cell type will grow in a particular batch of gel.

"The issue of reproducibility is a major one," said co-author Linda Griffith, PhD, professor of biological engineering and mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in a statement. "The research community has been looking for ways to do more methodical cultures of these kinds of organoids, and especially to control the microenvironment."

Organoid models for pancreatic cancer are especially challenging to grow. First, traditional gels do not readily support the growth of cancerous cells and their surrounding environment. Second, pancreatic cancer cells lose properties, such as their distinct stiffness, once they are removed from the body.

Formulating the gel

Griffith's lab at MIT has been working for 10 years on designing a synthetic gel that could be used to grow epithelial cells with more desirable and predictable properties.

Griffith and her colleagues formulated a gel based on polyethylene glycol (PEG), a polymer that is often used for medical applications, because it doesn't interact with living cells. Studying the biochemical and biophysical properties of epithelial and stromal cells and their interactions with the extracellular matrix (which surrounds organs in the body), the researchers identified features they could incorporate into the PEG gel to facilitate consistent cell growth.

The key biophysical property required to grow pancreatic cancer cells turned out to be strong adhesion between the gel and the cells in the organoid. The researchers found that incorporating small synthetic peptides derived from fibronectin and collagen in the gel allowed them to achieve the necessary "stickiness" required by integrins, cell surface proteins that mediate cell adhesion. The strong adhesion with the integrins allowed the cells to adhere firmly to the gel and form organoids.

Another key property of the gel formulation was its adjustable "stiffness," which makes it possible to recreate the characteristic stiffness of pancreatic tumors. By adjusting the gel's properties, Griffith and her colleagues reliably generated gel scaffolds that replicated the stiffness profiles of both normal and tumor-bearing pancreas tissues.

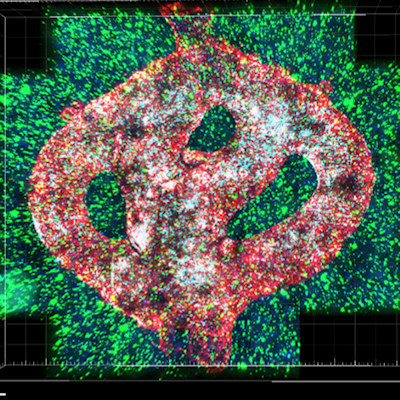

After developing the PEG gel, Griffith collaborated with Claus Jorgensen, PhD, who leads a team of researchers studying pancreatic cancer at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute, to test the gel and use it to grow pancreatic organoids derived from mice.

Jorgensen and his students were able to produce the gel and use it to grow both healthy and cancerous pancreatic cells.

"We got the protocol from Linda and we got the reagents in, and then it just worked," Jorgensen said. "I think that speaks volumes of how robust the system is and how easy it is to implement in the lab."

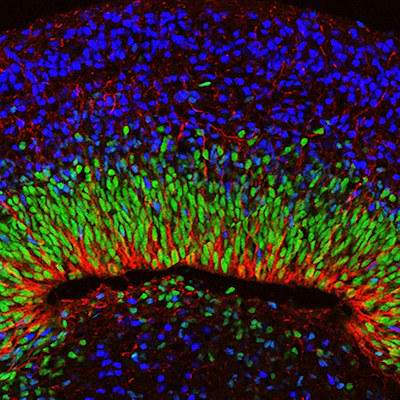

When Jorgensen and his colleagues compared the pancreatic organoids grown in the gel to tissues they had studied in living mice, they found that the tumor organoids expressed many of the same integrins seen in pancreatic tumors. Further, many of the supporting cells that normally surround pancreatic tumors were also present.

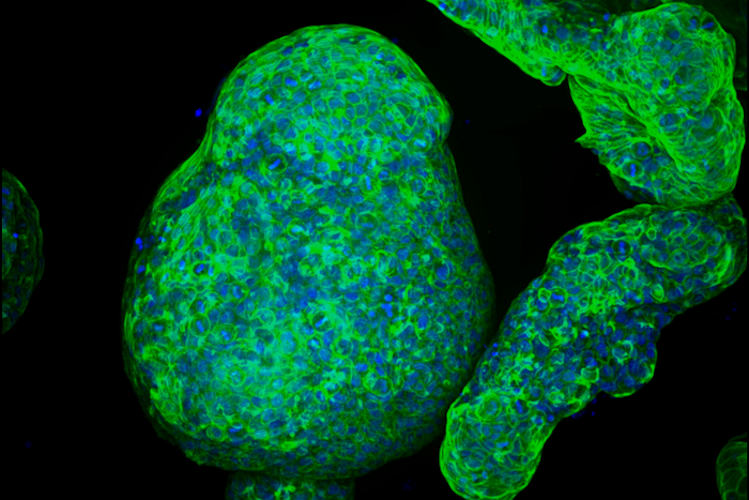

Following their success growing mouse cells, the scientists verified that the PEG gel would also support in vitro growth of human-derived pancreatic cells. They seeded the gel scaffold with established human pancreatic ductal organoids and monitored their growth. Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that the organoids grew continuously for several days, finally developing into fully mature spheres.

The researchers believe that the gel, which can be easily made in a lab, will prove useful for studying lung, colorectal, and other cancers.

Griffith plans to use the gel to grow and study tissue from patients with endometriosis, a painful condition in which uterine tissue grows outside of the uterus. She has filed a patent on the gel technology and is in the process of licensing it for commercial production.

Do you have a unique perspective on your research related to cancer research? Contact the editor today to learn more.

Copyright © 2021 scienceboard.net