September 26, 2019 -- For the first time, scientists have confirmed that bacteria can change forms to avoid being targeted by antibiotics in the human body. Researchers from Newcastle University used state-of-the-art technology to identify bacteria with this unique characteristic. They show, in a study published in Nature Communications on September 26, that these bacteria can survive without a cell wall, potentially leading to antibiotic resistance.

Urinary tract infection is a major cause of human disease costing over $1.5 billion a year in the United States alone. Antibiotics are the routine treatment options; however, they sometimes fail to resolve infection. Bacteria survival during antibiotic treatment, allows infection to reoccur after antibiotic withdrawal and potentially contributing to the antibiotic resistance problem the health industry faces. The World Health Organization identifies antibiotic resistance as one of the largest threats to global health, food security and global development in modern society.

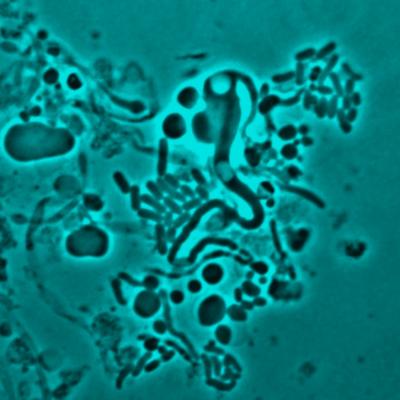

Bacterial cells are normally surrounded by a highly conserved cell wall made of peptidoglycans which defines their morphology. These cell walls are often the target for many antibiotic treatments. L-form bacteria are strains of bacteria that lack a cell wall. They are typically found a spheres or spheroids.

L-form bacteria are more difficult to identify by traditional methods therefore a special osmoprotective detection method is needed to detect weaker L-form bacteria in the lab. For this reason, they have been overlooked in clinical settings.

In this research, samples obtained from patients receiving common antibiotics such as penicillin (cell-wall targeting antibiotic) to show that bacteria have the ability to change forms. Previous research has shown that the human immune system can modestly induce L-form switching, whereas antibiotics induce a much higher effect of switching. Here, the team found that L-forms of various bacterial species associated with urinary tract infections including E. coli, Enterococcus, Enterobacter and Staphylococcus were detected in 97 percent of patients in the study. The L form bacteria identify in the study were flimsy and weaker than normal bacteria, but still some survived by hiding inside the body.

The data shows that L-form bacteria induced by the presence of antibiotic in urine or zebrafish larvae can revert to a walled state once the antibiotic is removed. The researchers were able to capture this transformation on video, observing L-form bacteria isolated from a patient with UTI re-forming a cell wall after the antibiotic had been removed (only five hours later). If bacteria are allowed the opportunity to re-form their cell wall, the patient can be at risk for re-infection. They suggest that this switch may be the reason why many patients face recurring UTIs.

Ultimately, the researchers suggest that L-forms could provide a source of bacterial survivors during treatment with cell-wall-specific antibiotics, independent of the need to acquire specific resistance genes. This led them to conclude that L-form switching might be an underappreciated mechanism of antibiotic tolerance by bacteria in other recurrent or chronic infections.

Do you have a unique perspective on your research related to bacteriology or clinical diagnostics? The Science Advisory Board wants to highlight your research. Contact the editor today to learn more.

Copyright © 2019 scienceboard.net