August 19, 2021 -- By adding a genetic on-off switch to engineered CAR T cells, researchers have developed a remote-controlled system that enables precision invasion of the tumor microenvironment for improved cancer-killing capabilities. The details of the research were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering on August 12.

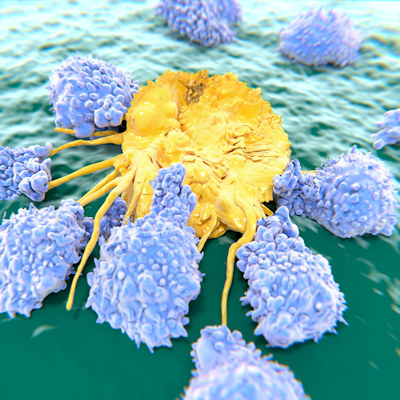

CAR T-cell therapy engineers a patient's T cells and adds a chimeric antigen receptor to specifically target and destroy cancer cells. However, CAR T therapies are not reliably delivered to solid tumors.

"These therapies have proven to be remarkably effective for patients with liquid tumors -- so, tumors that are circulating in the blood, such as leukemia," said Gabe Kwong, PhD, associate professor at the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. "Unfortunately, for solid tumors -- sarcomas, carcinomas -- they don't work well. There are many different reasons why. One huge problem is that the CAR T cells are immunosuppressed by the tumor microenvironment."

Many approaches use immunostimulatory agents, such as cytokines, checkpoint blockade inhibitor antibodies, and bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), to improve the antitumor activity of engineered T cells, yet they lack specificity and can be toxic to healthy tumors, which narrows their use cases. Thus, it is necessary to develop an approach that targets and locally activates CAR T-cell functions at tumor and disease sites.

Kwong and his team at Georgia Tech developed a technology for photothermal control of T-cell therapies. They constructed and screened panels of synthetic thermal gene switches containing combinations of heat shock elements and core promoters that respond to mild increases in temperature while maintaining cell function. The switches were designed to control a broad range of immunostimulatory genes, including BiTEs and a cytokine superagonist to enhance key T-cell functions, such as proliferation and T-cell targeting.

The team showed that thermal induction of transgenes is transient and reversible and that thermally activated T cells remain localized to heated sites while the transgene was expressed.

"These cancer-fighting proteins are really good at stimulating CAR T cells, but they are too toxic to be used outside of tumors," Kwong explained. "They are too toxic to be delivered systemically. But with our approach, we can localize these proteins safely. We get all the benefits without the drawbacks."

Enhanced antitumor responses seen

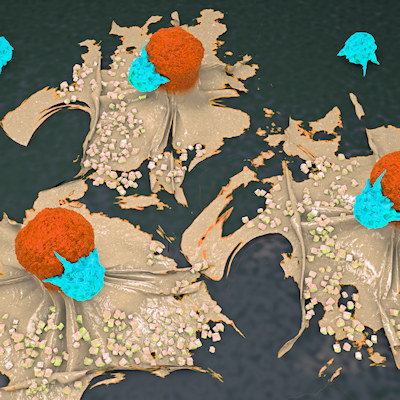

To demonstrate that the constructs could activate T cells by photothermal heating, the research team used plasmonic gold nanorods to convert near infrared light into heat. This well-studied nanoparticle has been shown to passively accumulate in tumors following intravenous administration. They injected mice with both CAR antigen-negative and antigen-positive tumors with the gold nanorods and the engineered CAR T cells containing the gene switches.

After 20 minutes of heat treatments, transgenes were expressed within tumors. Importantly, unheated tissues remained at baseline, indicating that transgene expression in the engineered CAR T cells was confined to heated sites.

Taking the therapy a step further, the team heated CAR T cells containing the thermal switch and an interleukin-15 superagonist (IL-15 SA) in vitro. These cells produced physiologically active levels of IL-15 SA following a single thermal treatment. Next, they transferred the cells to the mice with cancer. In vivo, the treatment led to a significant reduction in tumor burden and improved survival.

The researchers also tested heated CAR T cells containing the thermal switch and BiTE-targeting natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) ligands -- which are upregulated with a range of cancers -- as well as suppressor cells. In vitro, these cells secreted increased levels of T helper cells type 1 (Th1) cytokines interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) compared to controls. In mouse models of breast cancer, the adoptive cell transfer therapy resulted in significant tumor regression and protected against relapse.

In the future, the team will investigate additional strategies for tailoring T cells, as well as how heat will be deposited at the tumor site. In the current study, a gentle laser was used to heat the tumor site, but that won't be the method used when human studies are conducted.

"We'll use focused ultrasound, which is completely noninvasive and can target any site in the body," said Kwong. "One of the limitations with laser is that it doesn't penetrate very far in the body. So, if you have a deep-seated malignant tumor, that would be a problem. We want to eliminate problems."

Do you have a unique perspective on your research related to cell therapy or bioengineering? Contact the editor today to learn more.

Copyright © 2021 scienceboard.net