December 23, 2022 -- Sweden's Karolinska Institutet researchers have discovered that minute membrane bubbles called extracellular vesicles activate the immune system in mice, sensitizing their tumors to immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors. The study, published on Thursday in Cancer Immunology Research, supports the development of these nano-sized vesicles, also called exosomes, for potential cancer therapy.

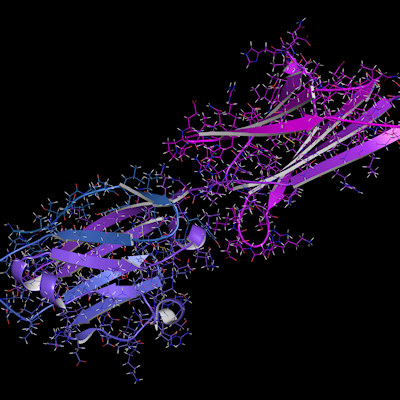

The body's cells send extracellular vesicles to one another as messengers that exchange information. Tumor cell vesicles, for instance, can switch off the immune system so the cancer can spread, while immune cell vesicles can activate an immune response. The vesicles make tumors immunologically active so that checkpoint inhibitors -- drugs that help the immune system's T cells attack cancer cells -- can gain traction and start to work.

The researchers examined the vesicles' functioning in a mouse skin cancer resistant to checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Extracellular vesicles were isolated from each mouse's own immune cells. A cancer-specific protein called ovalbumin and a molecule called alpha-Galactosylceramide, both of which stimulate T cells and natural killer cells, were then added.

When the vesicles were introduced into mice, either therapeutically to treat their tumors or prophylactically before their tumors began to develop, their immune systems produced strong T-cell responses to the cancer protein. This effect was not achieved if the mice were given only checkpoint inhibitors, and was most pronounced in mice receiving a combination of both vesicles and checkpoint therapy.

However, the boosted T-cell response did not increase survival rates in mice with tumors. Researchers hypothesize that the experiment's duration was not long enough for the activated immune system to affect the tumors. Prophylactic combination treatments of tumor-free mice, however, resulted in greater survival rates than those of mice that only received vesicles.

In previous studies on human cancer patients, the vesicles were safe but minimally effective -- perhaps because the scientists didn't yet know what molecules the vesicles needed to contain to work. The researchers are currently working on this question, along with trying to simplify the extracellular vesicle manufacturing process.

"Our aim is to be able to use cell lines instead of having to take the patients' own cells. This will mean that the vesicles can be prepared in advance and frozen until needed," explained Karolinska Institutet professor and co-author Susanne Gabrielsson, PhD, in a statement. "We also believe that variants of the treatment could be used for other forms of cancer and other diseases."

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net