October 30, 2019 -- Researchers from the University of Washington School of Medicine and Howard Hughes Institute found that gut bacteria acquire interbacterial defense gene clusters. The October 30 article in Nature, suggests that bacteria use these toxins against their microbial neighbors. This discovery could further scientific knowledge of the human gut which is critical to many aspects of health and disease.

Most commonly, diet and host immunity influence composition, but they cannot fully explain the entire microbiome. Direct interactions between co-residents also influence composition. Gram-negative order Bacteroidales encode the type VI secretion system (T6SS), which facilitates the delivery of toxic effector proteins into adjacent cells. These bacteria are the most predominant bacterial subtype found in the human gut.

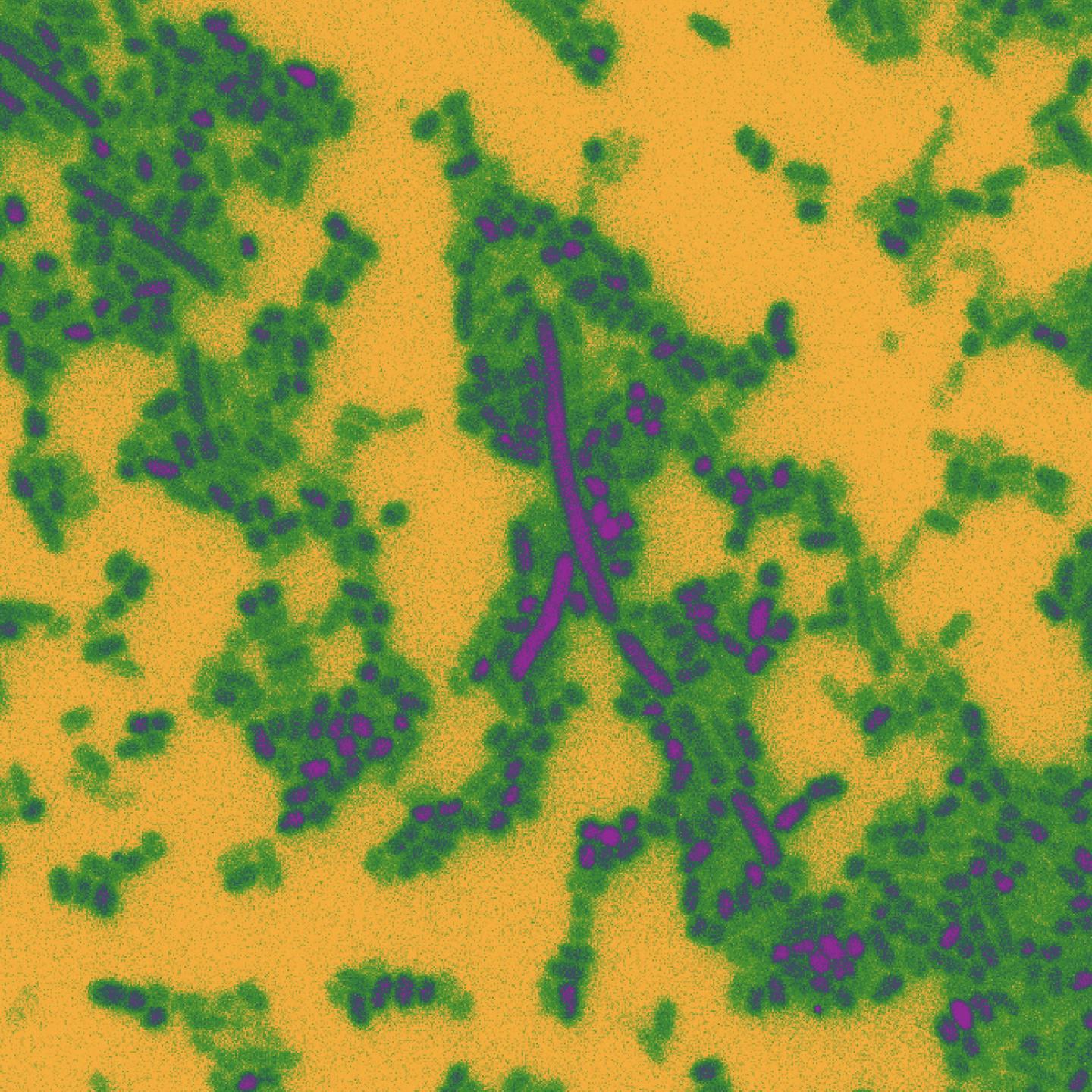

Researchers suggest that bacteroidales species acquire interbacterial defense (AID) gene clusters within the human gut. These clusters encode arrays of immunity genes that protect against T6SS bacterial antagonism. In some samples, the genes encoding immunity against a Bacteroides fragilis toxin were found in the bacteria itself. But in other samples, however, the genes appeared at higher levels that biomarkers for the bacteria. "This finding strongly suggests that these anti-B. fragilis immunity elements were encoded by other bacteria in the gut," the scientists explained. Some of these bacteria included: B. vulgatus, B. helcogenes and B. coprocola.

The gene clusters reside on mobile elements and provide sufficient resistance to toxins in vitro and mouse models. The scientists believe that these immunity genes have an adaptive role because they help these bacteria overcome toxic hits from their B. fragilis assailants. They see this shielding effect during growth in Petri dishes in their labs and when they introduced the bacteria carrying these genes into the guts of mice.

The clusters are located on the chromosome in a place that when mixed together with another bacterium, immunity genes were transferred and offered toxin protection. Therefore, the researchers propose that bacteriodales acquire gene for immunity from a variety of organisms.

The team also asked if other immunity genes to protect against toxins other than those made by B. fragilis. This led to the discovery of a second set of gene clusters that guard against toxins made by a range of different species.

The data suggests that acquiring orphan immunity genes through the AID system is a common way for gut bacteria to compete with other species and help to shape the human gut microbiome ecology.

Do you have a unique perspective on your research related to microbiome research? Contact the editor today to learn more.

Copyright © 2019 scienceboard.net